Recently I was browsing a used bookstore and remembered that I wanted to find a book on the 1910 avalanche in Wellington, Washington. Just then I glanced down and found Gary Krist’s The White Cascade: The Great Northern Railway Disaster and America’s Deadliest Avalanche. I’ve been drawn to this place for a while and needed to do my homework so I’d understand the true magnitude of what happened there.

If you have any interest in natural disasters, the Pacific Northwest, or Washington, U.S., or railroad history, this book, published in 2007, has received many favorable reviews. Its level of detail, which takes us chronologically through the disaster, was made possible in large part by the records passengers kept on the ill-fated Great Northern Train 25, the Seattle Express. For example, Krist said a running account was found in the wreckage with 29 year-old salesman Ned Topping’s body. Still recovering from the recent loss of his wife and unborn child, he’d been writing a letter to his mother.

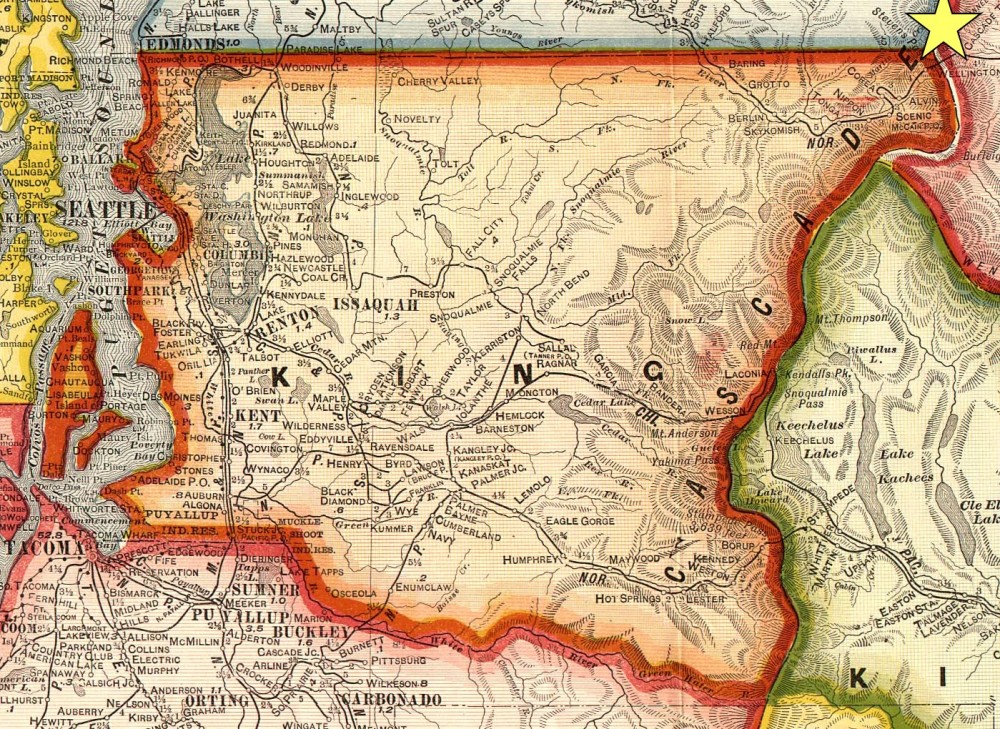

In 1910, young men and women would not have been sitting on a stranded train glued to their phones texting, “Dude, I’m so ___ bored. I need a beer. Where’s my XBox? LOL.” People actually took the time to write eloquent, heartfelt letters, and that’s what some passengers did as The Seattle Express sat stranded on the inside track next to Train 27, a mail train, on the edge of a sharp drop for about a week. A monstrous snowstorm had imprisoned them in this small railroad town 70-some miles east of Seattle. After they’d arrived in Wellington, they learned that an avalanche had taken out the shed where a cook and his assistant had graciously fed them on the other side of the nearby Cascade Tunnel. Both men were killed.

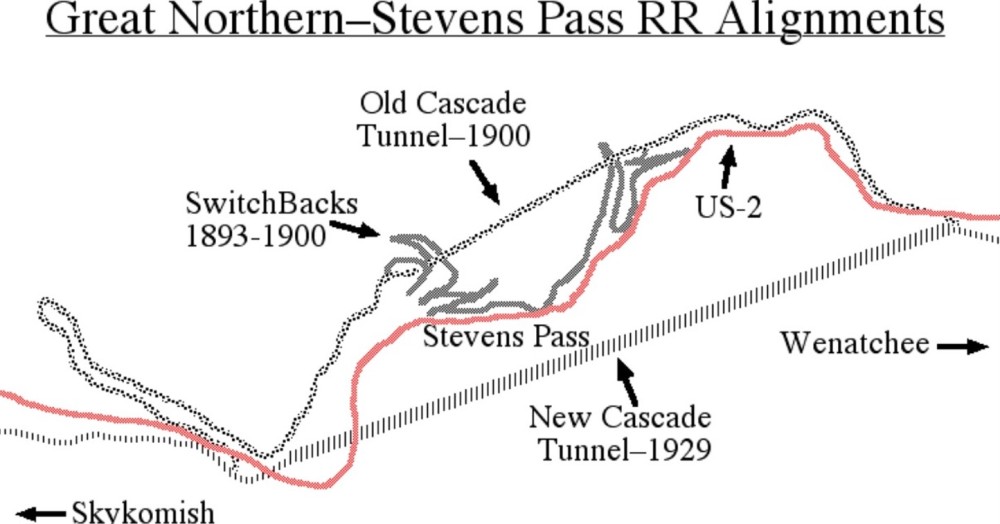

Despite the best efforts of the Great Northern Railroad’s supervisors and crew, the trains could not leave the area despite the catastrophic mass of frozen white building up on the sparsely covered slope above them. The trees on that slope were basically charred sticks thanks to a fire the year before and clear cutting in the area heightened the hazards. There was little holding this lethal frosting on Windy Mountain in place and some male passengers braved a death-defying 2000-foot slide down to Scenic, not wanting to stay on the Express. Some wanted the train put into the Cascade Tunnel, but that presented new problems, such as asphyxiation, sanitation, the longer distance people would have to struggle through to get their meals, and the risk of them being buried alive inside the tunnel. There was no good solution.

According to Krist’s book and other accounts, at 1:42 A.M. on March 1st, 1910, during a dramatic thunder and lightning storm preceded by heavy rain, a half-mile wide slab of snow broke off and came screaming through Wellington. The two trains, with about 125 people on board, as well as several locomotives, were swept off of the hill by the gargantuan wall of precipitation and debris. This was a 150-foot drop ending at the Tye River. Some smaller buildings in town had been blasted away by the avalanche as well.

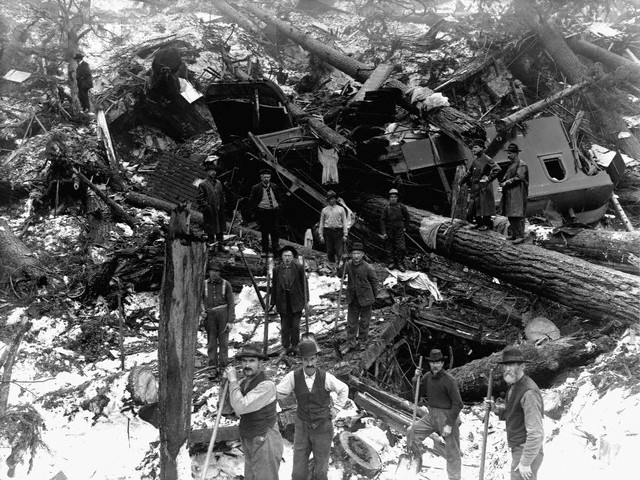

Survivors, railroad employees, and residents scrambled down the cliff in the raging storm to rescue whoever they could with whatever they had. Among the pulverized wood cars, sickeningly twisted metal, and giant downed trees, 96 people died that night. This is double the number of deaths caused by the March 2014 Oso mudslide. Not all of the Wellington victims died immediately. In terms of fatalities, it remains our country’s deadliest avalanche and one of America’s worst railroad accidents.

It took months to recover all of the bodies although most were found sooner than later– adults, small children, a baby who survived the initial event but died pinned under its mother, who was the last person rescued. I’ve seen estimates that there was from 40 to 70 feet of snow on the ground, and in an avalanche, that snow becomes like concrete. In time most of the wreckage was cleared away and Krist noted that the heavy locomotives were still in fairly good shape unlike the passenger and mail cars. The following year the Great Northern’s only all-concrete snowshed was erected at this site, carved into the hillside just next to where the original tracks were, spanning about 2600 feet. Other combination wood and concrete snowsheds were built to cover the line as it ambled west.

What is so remarkable about this story is that the 1911 snowshed is still there today, now part of the Iron Goat Trail system, and wreckage from this disaster is still strewn about the hillside. This isn’t a sterile chapter from days gone past, accessible only in two dimensions on the pages of history books. This is tangible, visible history in three dimensions. I don’t know why so much of the debris was left except that there is an average of 35 feet of snow here every year and nature quickly incorporated it into the peaceful woodland environment, with metal pipes and pieces now permanently embedded in huge trees.

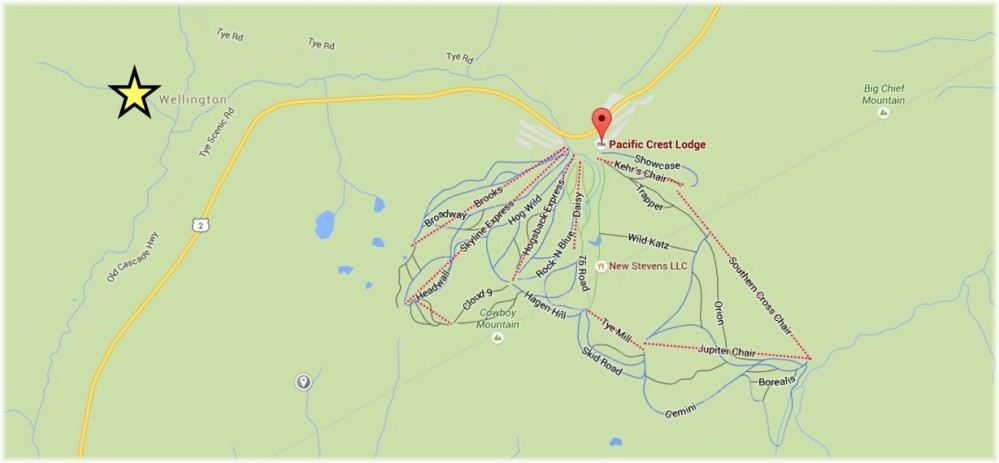

In 1929 the railroad built a new, much longer tunnel to the south to replace the original Cascade Tunnel and the strenuous switchbacks earlier trains had labored over. Post-avalanche, Wellington had been renamed Tye for PR reasons, and by the time the new Cascade Tunnel was built, it was a ghost town, its buildings eventually burned and lost. As the decades passed, Windy Mountain became heavily timbered once again, and animals regained their rule after a 40 year or so hiatus.

Today this is U.S. Forest Service land, and if you plan to visit, be sure to purchase a Northwest Forest Pass in one of the towns on the way in if you don’t already have one. A Discover Pass, for state parks only, won’t suffice. More on the various passes now required to do anything in the outdoors here, courtesy of the Washington Trails Association. (In the good old days, you’d just load the family into the trusty station wagon and explore the wilderness without worrying about the right permit.)

Yesterday local historian Matt McCauley and I decided to finally visit this site, which both of us had traveled past countless times on the crazily busy Highway 2. Upon arriving at the Wellington Trailhead parking lot, we were greeted by an authentic army tank, which the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) uses for avalanche control. I’d heard about the tank but was surprised to see it, the first of a number of surprises encountered at this site.

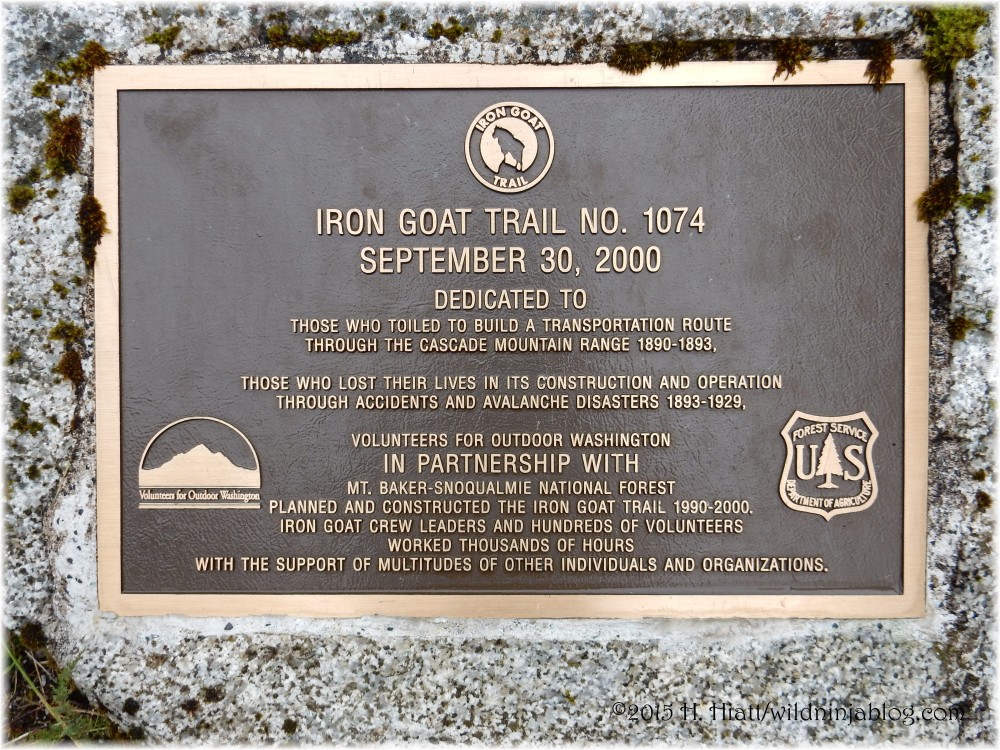

A plaque at the trailhead is self-explanatory.

It never fails that some knucklehead finds it cool to shoot up publicly-funded property. Several signs were damaged by various calibers.

At this point you are 1711 miles from the Great Northern Railroad’s headquarters in Minnesota. All mile markers would have been in this style a century ago. Thanks to one of the below videos for this information.

The entrance to the 1911 snowshed. The walkway was beautifully built. I had expected a basic path.

There was a notable amount of water damage and erosion in the snowshed. Mother Nature has been persistently chipping away at the structure.

More evidence of nature’s increasing dominance. I’m not entirely sure what the white stringy stuff was– I’m assuming mold.

They don’t make it like this anymore.

Inside the snowshed looking west. Once inside, you feel vaguely like you’re in an ancient temple.

Now who is this? This unexpected detail immediately struck me as pre-1930, perhaps even original from 1911. It was a delight compared to the trashy 1990s-style graffiti telling passersby that Steve was here. Way to trash a sacred site, Steve.

Two tracks ran parallel inside the snowshed. The modern trail was built on the inner track’s path. If I remember correctly, Martin Burwash said the original tracks would have been to the right (south) of the shed, literally on the edge of a steep drop.

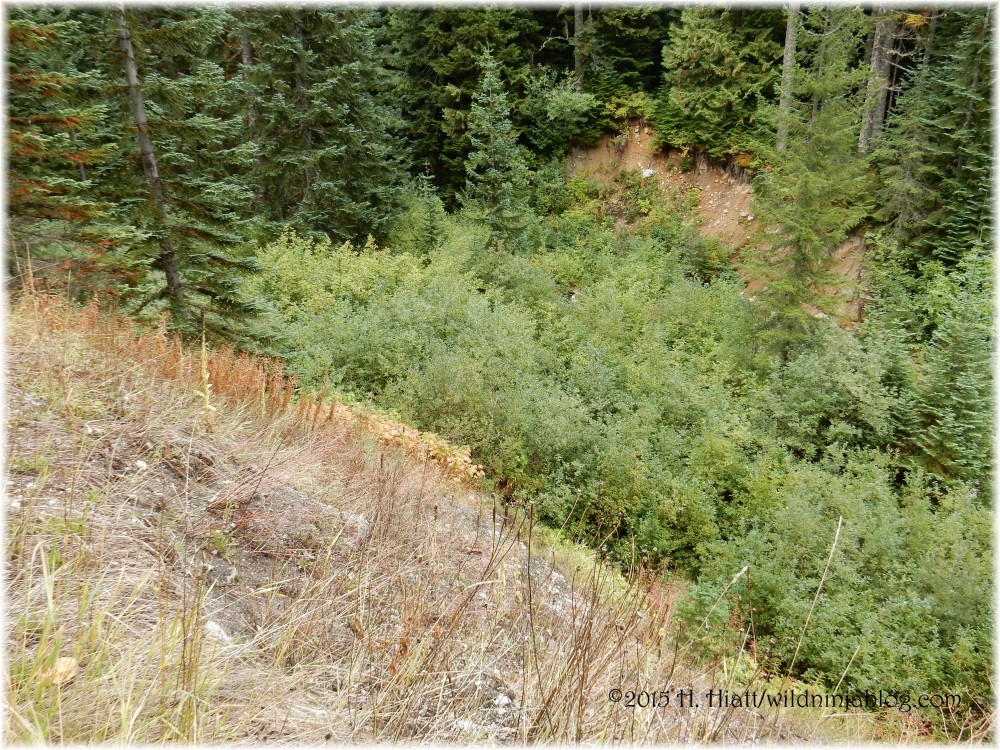

This lookout point sits in the middle of the disaster site. You can’t see anything through the trees, but simply being here is powerful enough.

I did not see any signs prohibiting entry to the steep hillside on which the wreckage lies. I’m still unsure if people are allowed down there or not. Given all the videos and photos on the web, it’s clear that small groups do brave the terrain, and there is a historic marker down below as if you’re expected. Note that the trail is slippery and dangerous, and I would strongly advise against bringing children and dogs to this site. There are far too many ways they could get hurt, and it would not be fun to haul a bleeding child in need of a tetanus shot back up this slope.

This site should be treated with deep respect; to me it deserves the same reverence with which you would visit a cemetery, meaning artifacts should be left where you found them, no one should be climbing on them or playing with them, and nothing should be removed. Tread lightly. I am not superstitious but don’t believe anything good would come out of removing any bit of this history. Almost a hundred people died here; a few parts of them are still here.

Note the pipe in the picture below. It’s everywhere– growing through trees, wrapped around trees, sticking out of the ground. You often can’t distinguish all the metal here from roots and branches, making it easy to trip over, and if you’re falling, to grab onto.

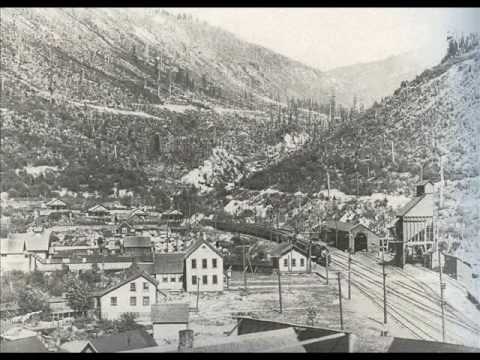

This is what this spot looked like in 1910. I’m not sure who to attribute the photo to as it appears so often on the web.

A railroad history buff could tell you what this is. I can’t. But it was obviously twisted by great force.

This hillside is littered with rusty debris, curiously clean old broken glass that didn’t come from bottles, and trees and poles felled by the avalanche.

My camera went a little fuzzy at times but it still captured the amazing sights.

How much more of this is buried underground? It’s not right to dig, though.

Debris still sits in the creek that leads to the Tye River.

This looks like it could have been dumped here yesterday. Was it really from the train?

Another photo of this slope 105 1/2 years ago.

Some of this metal might have been from a staircase… there were supposed to be several here.

This photo demonstrates the sheer force that ripped down this slope. The metal looks like a discarded piece of Iron Man’s prototype suit.

The Tye River. Some of the wreckage landed clear down here. Pieces can still be found in the river.

A stove. Supposedly there was one in every car (another reason it’s not a good idea for trains to be parked in circa-1900 tunnels). Update: I have been told this is a cook stove.

Wellington residents and railroad employees had to climb down this in the middle of the night, in the midst of a thunderstorm, in dozens of feet of snow, to rescue the survivors, some of whom were trapped in wreckage underneath old growth trees. The telegraph lines were down as well, so they had to hike out to ask for assistance. Getting assistance there was another problem.

One of several glass insulators Matt found. Some were still attached to cable.

This stump is referenced in multiple documents and videos. I wondered if it were the one the top half of three year-old Thelma Davis’ body was found lashed to by steam pipes as Gary Krist’s book had mentioned. The thought was a reminder that there are likely still a few human remains here. It was important to me to find this stump and pay my respects, especially to one so young.

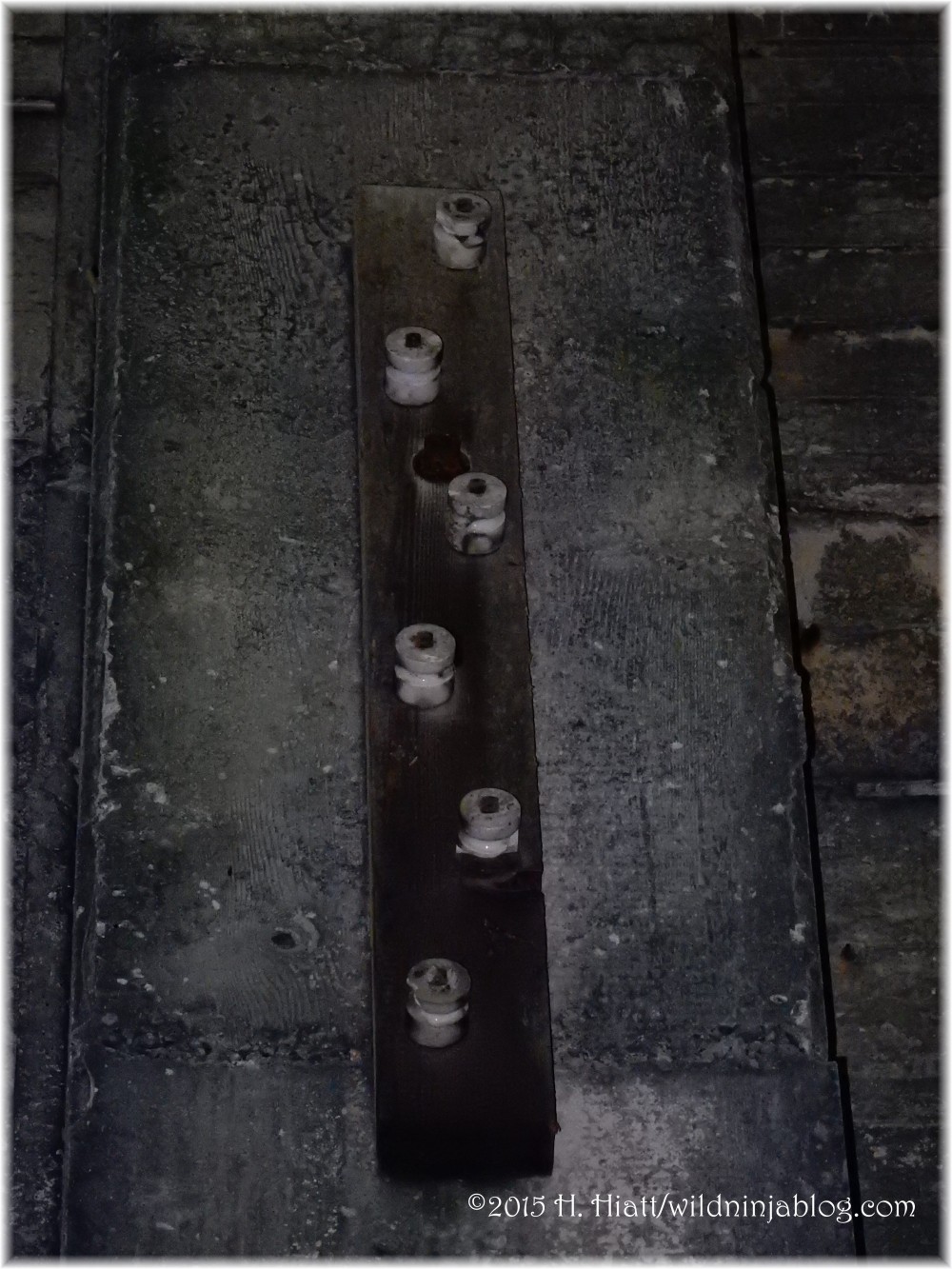

This appeared to be one of the junction boxes mentioned in Martin Burwash’s video.

There were a handful of mostly intact tanks like this across the slope.

This mesh had been explained in something I read or watched. Now I can’t remember what it is. Matt found a strip of old leather– from a seat, maybe?

This boulder is somewhat of a landmark at this site. Evidently multiple bodies were found here.

It was astounding to find pieces of metal still bearing their original paint and attached to pieces of wood that hadn’t decomposed yet.

Judging from the indentations in this tree’s bark, this piece has been there for a while. It should be left there.

The sentinel of the forest. While this is technically evidence of early logging practices, it seemed to be an observer, a solemn antique face watching over the hillside.

Someone forgot these… there was one abandoned work glove in the snowshed as well.

Looking at this, I thought, “what a beautiful rockslide.”

Then my hiking partner said, “No, look what’s in it. It’s buildings.” Krist’s book said several small buildings had been destroyed in the avalanche. Larger buildings like the Bailets Hotel and the depot were narrowly missed.

Once again, you think you’re looking at a rock, and it’s not a rock. You think it’s a branch, and it’s not a branch. There is a lot of man made material here.

Not a branch.

Martin Burwash said this brake part hasn’t changed much since then. Modern trains use a similar part.

Now to get back up there…

Back in the snowshed, continuing west, you can still see, high up on the wall, where wires would have been strung.

The west end of the snowshed, which was like some sort of post apocalyptic Mad Max modern art installation. Note the square rebar. There are signs warning of extreme danger and you should stay on the path. Fortunately a group of younger kids who’d gotten far ahead of their parents saw that. The youngest member of their group sat uncomfortably inside the tunnel as the older kids wandered on, explaining that she was worried about the lions. There are mountain lions and bears in the woods, so while I assured her the lions weren’t in the tunnel, if I were those parents, I’d keep that little one much closer for numerous reasons. As far as I know, I was the only Cougar in the tunnel just then (WSU!).

The view from the outside.

Highway 2 at Stevens Pass is just over yonder.

Adjacent to the concrete snowshed is the back wall of a combination wood and concrete snowshed. This trail goes for another five miles or so.

I’m still curious why the ends of the snowshed seem to be eroding so much more quickly than the middle section.

Heading back east. It’s like when you position two mirrors so that your view seems to go on forever. Except with the possibility of lions.

These leprechaun houses– well, drains, are evenly spaced along the shed wall. Some have far more moss growing on them than others.

Returning to the parking lot, you can then head in the opposite direction for more surprises. This was the coal bin that trains would drive up to for more fuel. Fuel became a problem during the days leading up to the Wellington avalanche because supplies couldn’t get through.

Once again my fellow adventurer spots something I passed… in this case, a piece of track sticking out of the hill near where the rotary plows were worked on. Can you find it?

Don’t know, but you find wonderful details like this everywhere.

Not a tree. I was tracing some cable lying on the ground and then noticed this.

These signs said this is the end of the trail. A rockery emphasized that. Within the last eight years or so, there has been a major collapse in the Old Cascade Tunnel and it sounds like there’s a significant amount of water inside. Signs said there is a flash flood risk. Note the trail and stones to the right.

These are the footings of the old water tower.

Despite all the warnings about flash floods, collapses, and what could be living in the Old Cascade Tunnel, which is about 2 1/2 miles long, I had to get closer. Again, I wouldn’t bring children back here. I don’t know how much longer until the whole thing collapses, and it could well collapse outward, not just down. If you feel compelled to hike a train tunnel, check out the Snoqualmie Tunnel off I-90 instead. I’ve hiked it, it’s awesome, and it’s only a dozen years younger than this tunnel, so about the same era.

Flash back 97 years ago and this is what this same spot looked like in 1918.

Another view, from a YouTube video that can be accessed by clicking on the photo. This appears to be from the Skykomish Historical Society. Skykomish is the next town down the pass (so if you’re coming from the Seattle-Everett area, you passed it and its glorious 1904 hotel that is rotting to pieces due to a legal dispute on the way up).

Unfortunately this tunnel’s demise was hastened by partiers who thought it was a good idea to hold raves inside. The loud music, particularly the bass, was a reckless move no matter how cool it looked.

It is readily apparent why you shouldn’t go inside. And there were inexplicable noises coming from deep within, like rocks dropping randomly into water. My spider sense got a little tingly here, like I was standing at the gates of the Mines of Moria and some tentacled evil was lurking in the water nearby. This is an ideal haunt for large carnivores.

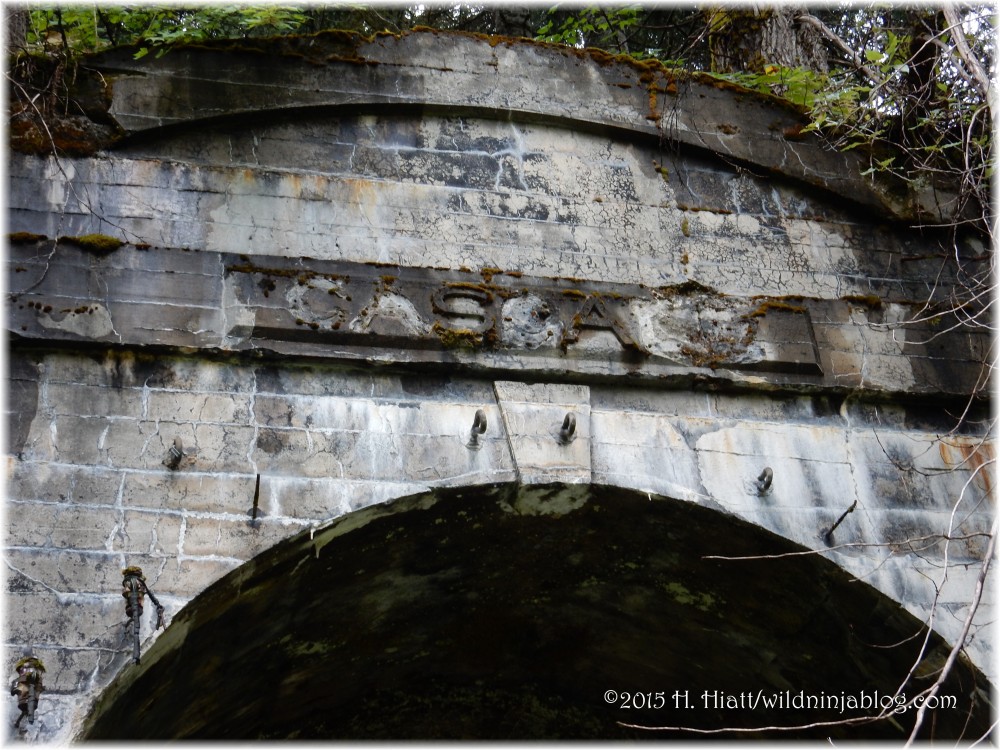

Only the S and A remain of CASCADE.

Debris in the creek that can become a river in the blink of an eye.

What’s behind door number one? And door number two? On either side of the tunnel there are what look like walled-in doors.

Nature is definitely tearing this down through slow, steady, instinctive effort.

While leaving, we were blessed with this visitor, who seemed as curious about us as we were about her.

I’d think that if the federal government really wanted to keep people out of certain areas they’d post no trespassing signs. I remain unclear on whether certain parts of this property were supposed to be accessible or not. Please use discretion as I don’t want to get in trouble for endorsing illegal activity.

Now I have a much better sense of how grievous the Wellington avalanche was. Seeing the site for myself, it really struck me how much danger Train 25 and Train 27 were in, how there was no good solution to their predicament, and how utterly dangerous the rescue and recovery efforts were on that slope with all that snow, the rain, and a freakish wintertime thunderstorm. My respect for what these people went through has deepened. They were intelligent, organized, and doing their best to find a way out. Tragically, some had decided to brave the death-defying slide to Scenic the next day. They never got the chance.

Here are some additional resources:

Exploring History in Your Hiking Boots has more information on this hike.

HistoryLink has an informative synopsis.

From the Seattle Times in 2010 for the hundredth anniversary, 1910 Stevens Pass avalanche still deadliest in U.S. history.

The Northwest Railway Museum has photos of the town I haven’t seen elsewhere.

Wellington is a magnet for paranormal investigators and I personally do not endorse this activity. There are angels and demons, but we are not meant to communicate with the dead and I certainly don’t believe they’re trapped here. The electricity in the air is not souls but the lingering aftereffects of so great of a sorrow and the rebirth of life. These people were somewhere else the moment their hearts stopped, so investigators should strongly question who or what might be talking back when they go looking. That said, this paranormal investigator compiled a nicely done video as a tribute to the victims of the avalanche. The historic photos are priceless.

YouTube user FistyCuff1 uploaded this video in January 2012.

Author and historian Martin Burwash gives a detailed analysis of the debris field and other parts of the site in this October 2011 video. Burwash has an interesting blog and has written a book about this disaster, Vis Major.

*************************************************************************************

“My God, this is an awful death to die,” said a voice in the darkness on the last car of the Fast Mail. –The White Cascade, Gary Krist

*************************************************************************************

©2015 H. Hiatt/wildninjablog.com. All articles/posts on this blog are copyrighted original material that may not be reproduced in part or whole in any electronic or printed medium without prior permission from H. Hiatt/wildninjablog.com.

love this thanks for your hard work! Deb Cuyle

LikeLike

Thank you!

LikeLike

Thank you for this beautifully-crafted piece. I appreciate your careful research and the photos. We humans are so fragile, despite our lofty endeavors.

LikeLiked by 1 person

So true. Thank you! That means a great deal coming from an accomplished author!

LikeLiked by 1 person